Technological Cartographies: Digital Colonialism in the Internet’s Territories

#algorithm #Big Tech monopolies #blogpost #climate change #Digital Colonialism #environment #labour rights #racism #smart cities #social environmental justice #surveillanceby Joana Varon

Text originally published at Digital Futures.

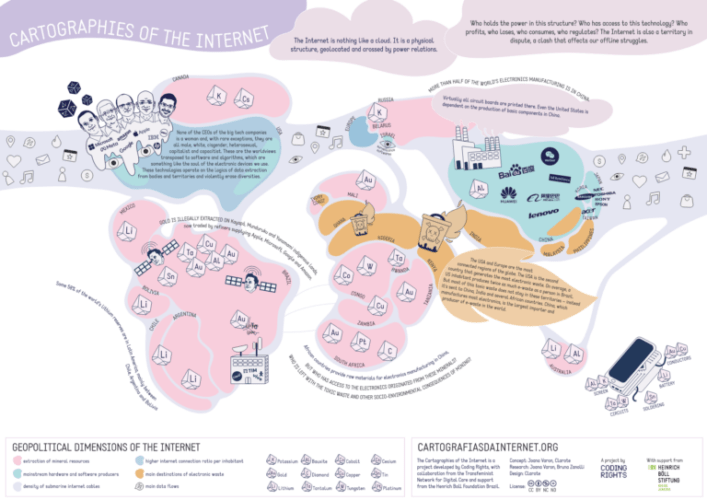

The Internet is nothing like a cloud. It is a physical structure, geolocated and marked by power relations. Cables, satellites, antennas, servers, computers, cell phones, minerals, toxic waste, energy consumption – enormous amounts of material, labour and decisions are needed to make it all work. The magical narrative of ‘the cloud’ feeds an imaginary that exists in the absence of a place or territory, and envisions the Internet as something immaterial, abstract, timeless and apolitical. Something very different to reality.

As we materialise the cloud, by developing a technological cartography that reveals and illustrates the physical and geopolitical dimensions of the Internet, we also expose the power relations that permeate its functioning, from the physical infrastructure layer to the sphere of algorithmic decision-making. Extractive relations, the practices of digital colonialism, and the establishment of monopolies become evident. We see that where we are, where we come from and who we are – across all dimensions of gender, sexuality, race, class, ethnicity, culture and nationality – matter in our relationship with this technology.

The internet is a disputed territory. These disputes affect the future of our democracies and which paths towards climate and socio-environmental justice are open to us. To play our part in these struggles, it is necessary to know its dynamics. To better know a territory, a map always helps.

During our session at the Digital Futures Gathering, we used the ‘Map of Internet Territories’1 as a tool to kickstart a debate about technology development that goes beyond the field of ‘digital rights’ to encompass the concepts and concerns of feminisms, climate change and socio-environmental justice movements.

Who holds monopolies in each part of the Internet’s structure? From which territories are the mineral resources that are key to today’s technological development extracted? Where does the e-waste go? What values are embedded in the algorithms of social networks? Who benefits from connectivity, who is left out? How much does digitalisation facilitate surveillance? Who has the power to surveil? Who profits? Who loses? How can the practices of digital colonialism be resisted?

Looking at the map, we can observe former colonial trade routes now overlaid by submarine cables. They tell us how internet connectivity is higher in countries with a history of colonising other regions as well as showing how closely today’s mineral flows between countries map onto those of the past. For instance, the Democratic Republic of Congo, Rwanda and numerous other African and Latin American countries continue to be the source of raw materials for electronics manufacturers located in China, which exports products and components to the whole world. Gold continues to be illegally mined on Kayapó, Munduruku and Yanomami Indigenous Territories in the Amazon region and is now traded by refiners who supply to Apple, Microsoft, Google and Amazon (the company that stole the name of a territory covering eight countries and several Indigenous people).2

The cartography also shows that about 58% of the world’s lithium reserves are in Latin America, mainly Chile, Argentina and Bolivia, the lithum triangle. So-called ‘green and sustainable’ technologies, such as the electric cars that are manufactured by Tesla and other companies, need lithium for their high capacity batteries. But who consumes the electronics that originate from these minerals? What are the impacts of these ‘green solutions’ on the territories of Latin America? Could these technologies ever live up to their claims of being clean and green? Who has to deal with the socio-environmental consequences of mining and the realities of toxic waste?

The map also shows that China, the biggest electronics manufacturer in the world, is the largest producer of e-waste. In second place is the USA – but unlike China, which is also the largest importer of e-waste, the US exports its toxic waste to India, China and countries in Africa. Europe too is present. Sharing one of the highest connectivity rates per inhabitant, it is also one of the biggest producers of e-waste, a fact made plain by The Nest Collective who shipped back containers of e-waste to Germany to produce the installation ‘Return to Sender’ for Documenta Fifteen in Kassel.

As some people become well connected and excited by what is dubbed by market strategists and tech billionaires as ‘green solutions’ and ‘innovation’, others get toxic mining, e-waste and poor connectivity. This problem cannot be solved solely by proposals which, while crucial, don’t address the bigger picture – for example, circular economy proposals or the very welcome approval of the loss and damage fund, which both the US and Europe were shamelessly pushing back on during COP27 in Sharm El Sheikh, Egypt.

Digital colonisation operates simultaneously, at multiple levels, from territories to imaginaries. As such it can be also be observed in the software layer of the internet’s cartographies, where dominance is enforced by the neoliberal tech bros of Silicon Valley cooperating with the hidden practices of surveillance capitalism, and more recently by Chinese companies, operating in a context where the lack of concern for human rights is a bit more explicit.

Dependency on tech monopolies has rotten democracies. Their business model profits from hate and misinformation which matches perfectly with the strategies of the far-right. For example, in the recent Brazilian presidential election, the media strategy of the far-right candidate included sponsoring Google ads with misleading information about the deforestation rate in the Amazon region. Deforestation increased 73% in the first three years of his mandate as president, but misleading ads portrayed it as higher during the period when the opposition party were in power. When questioned on a TV debate about his policies to protect the Amazon, the far-right candidate lied, saying that deforestation rates had decreased and told people, ‘Just Google it’, in full awareness that the top result would most likely be the misleading ads. In just ten days, his campaign spent more than 3.3 million dollars with Google alone. Just pause to consider how profitable an election fuelled by misinformation is for Google, or how accountable Twitter is under Elon Musk. The list goes on…

Any attempt to envision better digital futures should start from understanding and acknowledging the process of digital colonisation that is in progress.

So, during the first meeting, we mapped additional layers onto the cartography, among them language, energy consumption, content moderation and regulation. Searching for hope, the second meeting became a quick-fire exercise in mapping existing resistance initiatives such as feminist collectives, wireless community networks, antiracist movements in tech, decolonial practices and manifestos, design justice practices and disability tech. There’s a long way to go…

Cartographies are living experiments. Maps change as territories change. In our digital futures, I hope the cartographies of the Internet Territories acquire different shapes that are more diverse and less extractivist, which recognise other values as guides for tech development, that are feminist and decolonial, that seek social justice and collective rights, and are respectful to all cultures and living beings, including the Earth.

Joana Varon is Executive Directress and Creative Chaos Catalyst at Coding Rights, and affiliated to the Berkman Klein Center for Internet and Society at Harvard University. From 2020-2022 she was a Technology and Human Rights Fellow at the Carr Center for Human Rights Policy at Harvard Kennedy School, and is an alumni of the Mozilla Fellowship. Brazilian with Colombian ancestry, she is co-creator of several creative projects operating at the intersection between activism, arts and technologies, such as cartografiasdainternet.org, transfeministech.org, chupadados.com, #safersisters, Safer Nudes, protestos.org, Net of Rights and freenetfilm.org

1: Developed by Coding Rights and accessible to download at cartografiasdainternet.org, the Map is a work in progress initiated through a workshop held in partnership with the Transfeminist Network of Digital Security Trainers during the Panamazonic Social Forum – FOSPA, hosted in Belém do Pará, Brazil, in July 2022.

2: When Amazon filed a request at ICANN to register the top level domain [dot]amazon, Brazil and Peru filed a complaint, arguing the address should be associated with issues involving the region. The complaint argued that: ‘Granting exclusive rights… to a private company would prevent the use of this domain for purposes of public interest related to the protection, promotion and awareness raising on issues related to the Amazon biome.’ It also stressed that ‘It would also hinder the possibility of use of this domain to congregate web pages related to the population inhabiting that geographical region.’ After long years of dispute, the interests of the Big Tech prevailed over a region. Source: Early Warning submitted by Brazil and Peru to the Governamental Advisory Board at ICANN.