The Future Is TransFeminist: from imagination to action

#blogpost #consent #speculative futuresby Joana Varon

Article originally published at Deep Dives

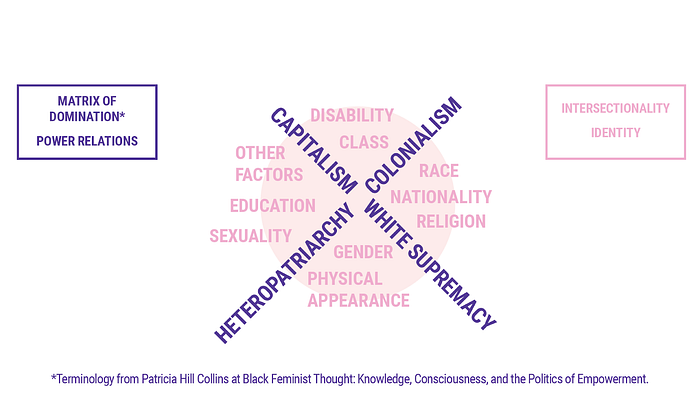

For the last few years, inspired by creative exchanges with feminists from different spots around planet Earth, I’ve started to play with the idea of envisioning speculative transfeminist futures. What would the future look like if algorithms that command our daily interactions were developed based on feminist values? What if the technologies we cherish were developed to crash, instead of maintain, the matrix of domination of capitalism, hetero-patriarchy, white supremacy, and colonisation?

Throughout history, human beings have used a variety of divination methods — as technologies — to understand the present and reshape our destinies. Such as tarot decks. At Coding Rights we’ve developed the Oracle for Transfeminist Futures in partnership with mediamakers and scholars Sasha Costanza-Chock and Clara Juliano. This virtual and physical card game is a playful tool designed to help us collectively envision, prototype, and share ideas for alternative imaginaries of futuristic technologies. The values that we explore in this game include agency, autonomy, empathy, embodiment, intuition, pleasure, and decolonisation. While these values have emerged from workshops with feminists in Latin America, North America and Europe, the game itself was inspired by a speculative feminist writing workshop with Lucia Egañas, contemporary design ideation practices that Sasha writes about in her book Design Justice and methodologies from a research group at the Internet Engineering Task Force.

We like to say that the wisdom of this Oracle, embedded with transfeminist values, can help us foresee a future where technologies are designed by people who are too often excluded from or targeted by technology in today’s world.

* * *

I’ve always loved technology and how it has played a role in my imagination of futures. Looking back, it’s easy to remember me pretending that my rubber, ruler, pencils and pen were the controls of a spaceship that I was driving while in the middle of a Math class. A few years later, I was amazed that I could visit those other worlds in video games. It also felt strange that there were mostly boys in the rooms where we used to gather to play Atari.

Strange, but comfortable. ‘Maybe, I was a bit strange too,’ was my thought.

In the eighties, my dad and I got hooked on colourful Mario Bros, over the then-recently launched Nintendo NES. Japanese tech and media all the way. That innovative console could reach me in the closed Brazilian IT market only because many Colombians had family members in Miami — I had that privilege. My aunty played a role in guaranteeing my access to the latest tech. In my mind, Japan was the future, full of robots and games that I always wanted to play and see. But all those imaginaries still continued to feel very gender-normative, to which I was misfitted. Why did I always need to be Mario or Luigi? Why did we need to save the princess? Why was the princess not using her own strength and tools to unblock her own path? Why was it always a blond white pinkly dressed princess who needed to be saved? Why couldn’t the princess save another princess? Why couldn’t I save the turtles from Mario instead?

The nineties came with the arrival of Chinese video game cartridges in Brazil, amazingly filled with more than 50 games in one, much cheaper, but all with very controversial copyright practices. Another life hack to access content. We could play a wide variety of sports games on these, but in none of these did I have the option to be a non-male avatar. It was only when personal computers came to Brazil that I finally had something non-gendered to play and freely lose my imagination in — from the black-and-green screen running MS-DOS to word editors and PaintBrush.

When the Internet finally arrived, it was like magic — we could suddenly have access to almost any book or song we wanted. I didn’t need to wait for ages or bother my aunty in Miami to get that new album from that British rock band. Even better, on MySpace or PirateBay, I could listen to tunes peered by online communities. Maybe a garage band that I’d never heard of but was creating our own style of rock and roll rioting and complaining about our own realities, be it from Sao Paulo, Porto Alegre or Buenos Aires. We could use blogs to write things anonymously for unknown people to read and comment on. There was a positive feeling of autonomy and horizontality emerging, in which we were transforming from media consumers to media creators, finally able to queer genders and let our imagination fly loose with those new tools.

Sounded like tools for revolutions.

But that was when I came across an invitation to join a platform called Facebook. I didn’t know then that its origins lay in FaceMash, a sexist ‘hot or not’ game developed by Mark Zuckerberg. Harvard students used FaceMash to compare pictures of two female students side-by-side and decide who was more ‘attractive’. Facebook’s history takes it from a sexist game to legal suits for privacy violations to complaints about weak content moderation around racism, xenophobia, sexism and violence.

This is living proof that values matter when we design technologies. That people involved in creating it matter. That context matters.

***

Facebook. Google. Apple. Microsoft. Amazon. As the white male-dominated Big Five in Silicon Valley monopolise most platforms that guide online interactions almost everywhere outside China, any aspiration towards a feminist revolution has become capitalised. The Big Five use terms such as ‘community’ while what they actually want is to turn us into addicted ‘users’ — with our desires becoming the products and targets of those running what black feminist scholar Patricia Hill Collins calls the matrix of domination.

The last ten years of the internet have seen many threats. Beyond Snowden’s revelations on mass surveillance, we have seen coordinated sexist online attacks on feminists, women journalists, non-male gamers, female politicians or vocal women; Google searches pointing to racist results; the Cambridge Analytica Scandal signaling how targeted ads can threaten democracies with misinformation; the Uberization of work that dismantles any enforcement of labour rights; governments and private companies engaging in censorship at the DNS level, such as the recently mapped blockage of abortion webpages in Brazil, or even through automated decision-making processes that end up silencing voices of dissent.

What’s more, the use of Artificial Intelligence for content moderation seems to be very hetero-normative. Instagram censored the harmless dancing frog below that Coding Rights posted on 29th August, the day of lesbian visibility in Brazil. It seemed that the algorithm had flagged the word sapatão, which literally means ‘big shoes’, but sometimes is reduced to ‘sapa’, or female frog. In Brazilian Portuguese, sapatão has been translated as ’dyke’ and re-appropriated from an offensive word to become a means of self-identification among lesbian women. After this episode, other lesbian collectives and activists stated that they had faced similar sapatão blocks.

The emergence of what scholar Shoshana Zuboff calls Surveillance Capitalism has also opened digital space to practices of gendered surveillance: threats by partners who spy on devices; a web full of ads that hiddenly reinforce gender roles; policemen infiltrating dating apps and period trackers that turn our blood into money (for others) or are even funded by the anti-abortion movement to spread misinformation that prevents access to sexual and reproductive rights.

These are the trends and values that are taking us to the next phase where in addition to our devices, our bodies are also becoming data sources. From facial recognition to the Internet of Things and the collection of DNA information, datasets about our bodies are being linked with data collected from our digital interactions on platforms. Under the narrative of innovation and security, this is taking profiling and discrimination to another level. From the results of contact tracing and COVID19 immunity passports to enable free movement across territories to sexist AIs that moderate access to welfare services, it is likely that most of our interactions with both public and private services will become mediated by biased algorithms carrying over structural inequalities disguised as neutral mathematical operations. This is what mathematician Cathy O’Neil has named ‘weapons of math destruction’.

But destruction goes even beyond data extractivism and data colonialism. Developed mostly in the North, these technologies are dependent on (conflict) minerals and metals that are sourced in the South. Later on, these technologies turn into toxic waste that is also trashed on Southern lands. And as databases become bigger and bigger, the processing power of Big Data demands even more energy. But even beyond all these production cycles, as highlighted by indigenous leader Vandria Borari and decolonial feminist scholar and journalist Camila Nobrega, during their insightful and disruptive presentation at Reboot Earth: technology might end up threatening different ways of existence.

As indigenous leader, Alessandra Munduruku said in an interview to Camila: ‘Sustainable development never existed for us. In order to build a hydroelectric plant (‘green energy’), it is necessary to deforest and flood. (…) A protected forest means it must not be cut down. And we don’t want the internet…if it means destroying our territory. We have to be heard when we say how we want things to be done.’

***

Imagination is a tool for revolution. We cannot change unwanted trends if we do not envision alternatives. Feminist science fiction writer Ursula Le Guin has, among other things, exposed how boring and limited is the world view in which gender is solely a binary concept. She once said: ‘The thing about science fiction is, it isn’t about the future. It’s about the present. But the future gives us great freedom of imagination. It’s like a mirror. You can see the back of your own head.’

That is what we are seeking with the Oracle for Transfeminist Futures.

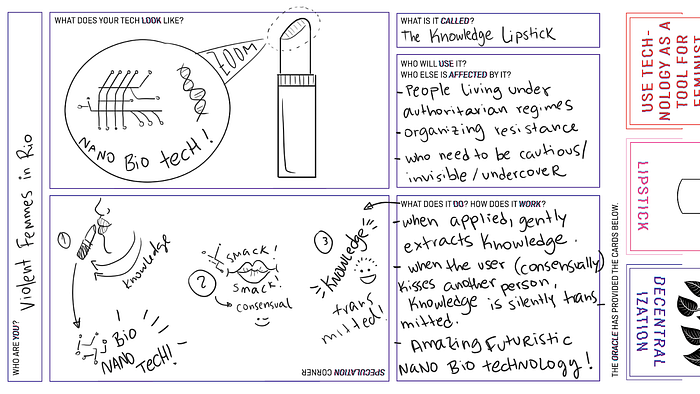

Take this amazing knowledge lipstick (just above) for example, which we’ve imbued with one of our transfeminist values: decentralisation. People who are living under and organising against authoritarianism need to be cautious when transmitting information. In other words, information transmission needs to be decentralised — or distributed — to lower risk. What if we could use lipstick as a low-risk way to spread information? What if we could use nanobiotechnology to build a lipstick that transmits selected knowledge from the person who wears it to another person who is consensually kissed. That’s an example of how we re-imagined technology while playing with the Oracle’s tarot cards.

I believe we can also turn these imaginative exercises and feminist values into action. In fact, Chilean feminist researcher Paz Peña and I have been doing just that around consent. In this paper we explore how feminist concepts of sexual consent can feed into the data protection debate ‘in which consent — among futile “Agree” buttons — seems to live in a void of significant meaning.’

We attempt to bring ideas around power to debates around consent and data bodies. In order to do this, we’ve looked at feminist attributes of consent and the attributes of consent from prominent data protection debates, such as in the European General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR). We then built a matrix comparing both. Through this exercise, we found that some consent attributes do overlap between feminism and data protection, such as: intelligible, informed, specific, freely-given.

However, we also found that consent in data protection laws combine all these attributes into a single action of clicking a button. And that click typically has only a binary option: Yes/No. This individualistic and universal view of consent doesn’t address structural issues, including an inequitable power relationship between us and the platforms we use. This, ultimately, challenges our ability to say no.

As feminist scholar Sara Ahmed says: ‘The experience of being subordinate — deemed lower or of a lower rank — could be understood as being deprived of no. To be deprived of no is to be determined by another’s will.’

If, in clicking no, we are doomed to exclusion from the service, we can say we are deprived of no — and of consent. The question that then stands in front of us is this: How can we build technologies based on feminist notions of consent? And going beyond consent, how can we use feminist frameworks and values to question, imagine and design technologies?

This is a two-part essay. In part 2, Joana Varon chats with Catherine D’Ignazio, the co-author of Data Feminism, about the relationship between feminism, power and data.

Joana Varon is Founder Directress and Creative Chaos Catalyst at Coding Rights, a women-run organization working to expose and redress the power imbalances built into technology and its application, particularly those that reinforce gender and North/South inequalities. Currently, she is also Technology and Human Rights Fellow at the Carr Center for Human Rights Policy from Harvard Kennedy School and affiliated to the Berkman Klein Center for Internet and Society at Harvard University

This work was carried out as part of the Big Data for Development (BD4D) network supported by the International Development Research Centre, Ottawa, Canada. Bodies of Evidence is a joint venture between Point of View and the Centre for Internet and Society (CIS).